Warming up, cooling down and stretching should be straightforward but, as with so many things in the world of fitness, once you start looking into them you soon find yourself bogged down by all sorts of mind-boggling terminology (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, anyone?!) that all seems to get in your way and conspire to make it difficult for you to simply find out the basics.

Therefore, in this article we’re going to look at how to structure a workout, including where to do the different types of stretching, in order to make it as safe and efficient as possible. It should be useful to PTs looking to structure sessions, but if you’re looking for an even easier-to-follow guide to warming up and stretching, you can find one here.

Warm Up and Cool Down

First of all, let’s look at the differences between a warm up and a cool down.

As their names suggest, the first is performed to warm up your body in preparation for a workout and the second is performed to bring your body back to normal after a workout.

To summarise the main aims of a warm up and a cool down:

A warm up should raise your pulse, get your blood flowing quicker, warm up your muscles and mobilise your joints. All these things are done to help your body cope with the demands of a workout.

A cool down should lower your pulse, slow down blood flow and return the muscles and joints to their previous state.

Essentially, you’re pretty much doing the opposite at the end of a workout to what you did at the start.

Mobility Exercises

The best way to start a warm up is by doing what are called mobility exercises. These involve performing controlled movement of the joints (rather than the muscles) in order to prepare them for exercise.

They are performed carefully and under control and should stay within the joint’s range of movement rather than trying to push beyond it.

Examples include rotating the hips or swinging the arms backwards and forwards across the chest. Here’s a video of a good full-body mobility warm up:

Safety point: mobility exercises are about warming up the joints rather than stretching the muscles so, as well as being performed under control, should not involve pushing to a point of discomfort or pain.

The Different Types of Stretches

Now let’s look at stretching. Stretches are broadly split into two categories:

Dynamic stretches

These are where you move the muscle you’re working until you feel the stretch, such as swinging your leg forward to activate the hamstrings. The idea is to try to push a bit further each time, so in the case of a leg swing you’d try to go a bit higher with each one.

Dynamic stretches are usually performed before a workout, to increase the muscles’ range of motion as well as warming them up.

(Note: whilst dynamic stretches are aimed at the muscles and mobility exercises aimed at the joints, in practice there is a fair amount of crossover between the two types of move, and some warm up exercises will do both.)

Static Stretches

These are where you hold the same position for a set amount of time (such as holding your arm across your chest for fifteen seconds). These are further divided into:

- Maintenance stretches, where you stretch the muscle to its usual point of resistance and hold it there, which is done to return a muscle that has been worked to its usual length. These are normally held for 10-15 seconds.

- Developmental stretches, where you stretch a muscle beyond its usual point of resistance, which is done to increase and develop its flexibility. These are normally held for at least 15-30 seconds.

Static stretches are usually performed after a workout, in order to restore the muscles to their pre-workout length or increase their overall range of motion, with current thinking being that doing them before a workout may actually hinder your performance. (One exception, however, is that if you have a particular area with tightness or restrictions, such as hips or hamstrings, then you may wish to perform some static stretching on that prior to your mobility section so as to increase its range of motion during the workout.)

As with everything else in the gym, prioritise safety. Don’t stretch to an uncomfortable point, and stop if you feel any pain or discomfort. Remember: stretching and mobility are there to make things safer, not more dangerous.

As an example, here are two videos demonstrating post-workout maintenance stretching, the first focusing on the upper body:

And the second focusing on legs:

Pulse Raising and Pulse Lowering

At the start of a workout, as part of the warm up, you can perform what’s called a pulse raiser.

A pulse-raiser is essentially a cardio move, but one performed at a lower intensity than it would be when performed in the actual cardio section of a workout, in order to get the blood flowing quicker and raise the heartbeat. For example, you might run on a treadmill for two minutes at an effort of 3/10, whereas for a ‘proper’ cardio section you might do ten minutes at 7/10.

This is a good idea if you’re going to be doing a higher-intensity workout, such as one involving HITT, where the heart rate will be significantly elevated, as it means you’re not suddenly jumping from your resting heart rate to a much higher one, but are instead increasing it in stages. It may not be as necessary if you’re doing a weights-based workout, but in that case you may still wish to perform a short pulse-raiser such as doing some quick bodyweight squats just to increase the heart rate.

After the workout, as part of the cool down, you’d perform a pulse-lowering exercise, which is very similar except the purpose is to bring your heart rate and blood flow back down to their normal levels in order to return your body to its pre-workout state.

The pulse lowering section can be the same as what was done as the pulse-raiser in terms of the duration and intensity, ie a few minutes on a treadmill at a 3/10 level of effort.

And, again, if you’ve done a weights-based workout then a pulse-lowering phase may not be necessary; it’s a good idea to do one if you’ve carried out a high-intensity session where the heart rate was raised a lot, but if you’ve focused on weights then the static stretching should be enough.

Where Everything Is Placed Within a Gym Session

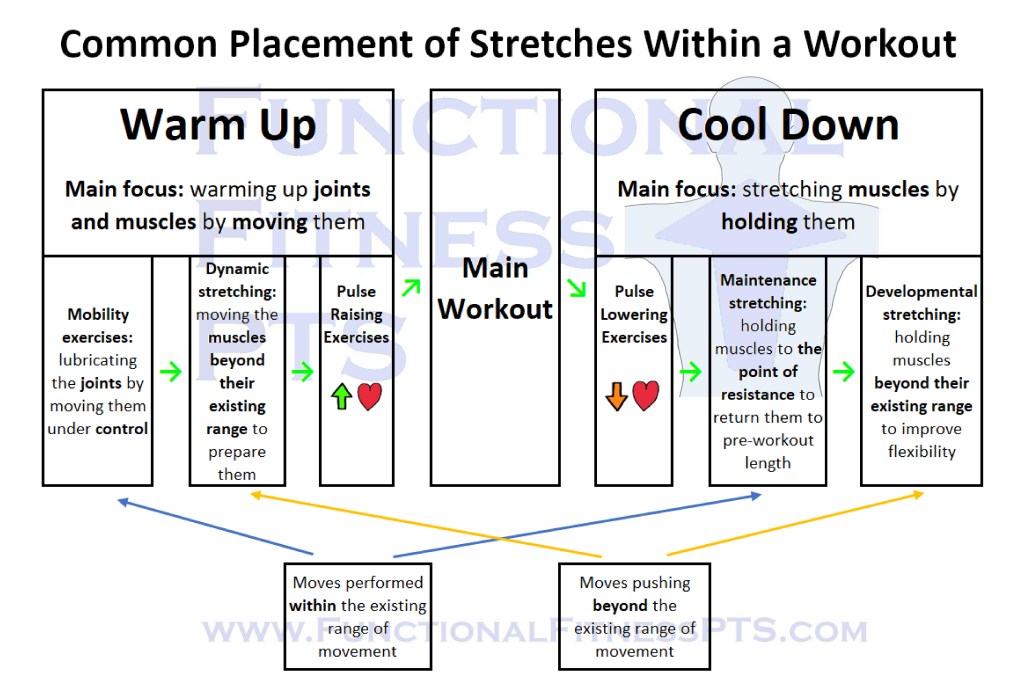

So now we’ve looked at all the individual elements of a warm up and a cool down let’s put them together! A common way to structure a session is like this:

Begin With a Warm Up, comprised of:

- Mobility exercises, warming up the joints within their range of movement.

- Dynamic stretching, warming up the muscles by moving them beyond their range of movement. (These are often done at the same time as the mobility exercises due to their similarities.)

- Pulse raiser, raising the heart rate and increasing blood flow. (This is optional depending on what type of workout you’re doing.)

Do The Workout (Weights and Cardio Exercises)

Finish With A Cool Down, comprised of:

- Pulse lowering, reducing the heart rate and blood flow. (Also optional, depending on the intensity at which you worked.)

- Maintenance stretching, returning muscles to their pre-workout length.

- Developmental stretching, pushing muscles beyond their existing range of motion to improve long-term flexibility.

And here’s a table that brings together everything we’ve covered:

You may also have noticed a number of analogies between warm ups and cool downs beyond how you’re doing the opposite in one than you are in the other, and you can draw comparisons between:

- Mobility exercises and maintenance stretching, because even though they’re performed on different sides of the workout, they’re both about working within your existing range of movement.

- Dynamic stretching and developmental stretching, because even though they’re also performed on either side of the workout, and one is moving whilst the other is static, they’re both aimed at increasing a muscle’s range of motion.