This is another of those slightly odd topics they make you learn at Level 3 even though it doesn’t appear to have any obvious uses in the gym. However, once you get your head around the principles you start to see there are some practical applications, so it’s still worth knowing.

So, within the human body the joints function as levers. You can think of the elbow as being a hinge as it’s where the movement happens.

Basic Terminology

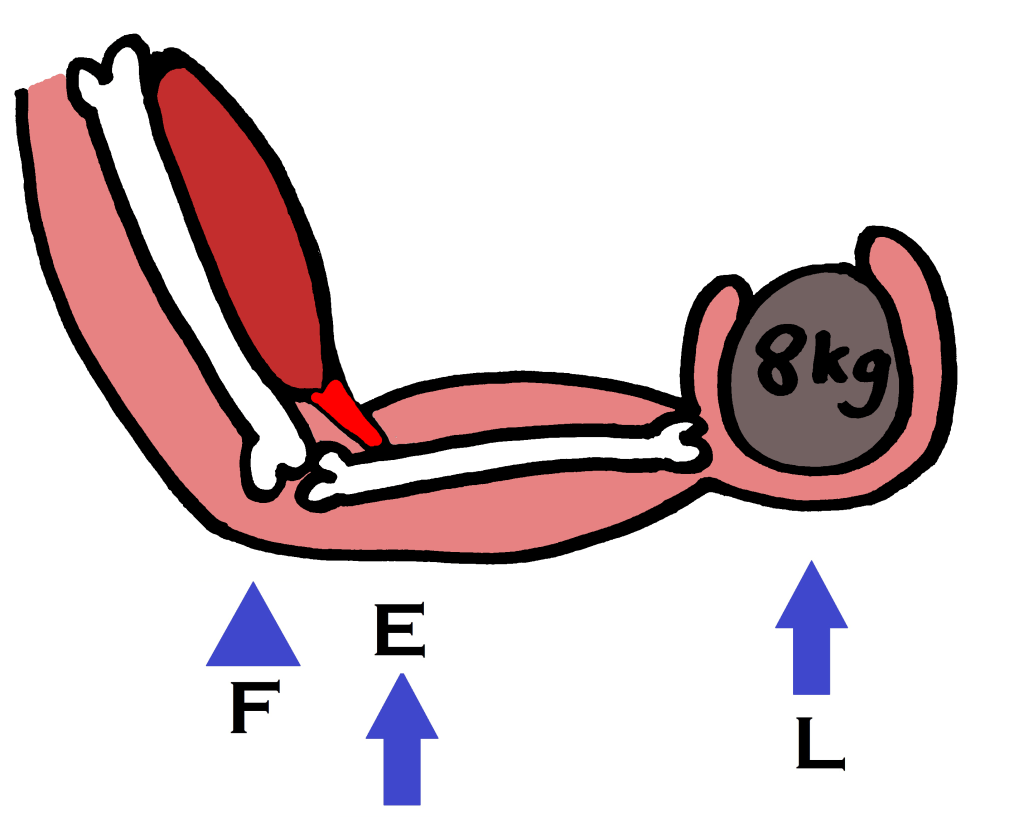

The terms used when referring to levers are:

- Load (L): this is the resistance, so what is being moved. In a lifting exercise this would be the weight.

- Effort (E): this is the force being applied to lift the load. In an exercise this would be the muscular contraction.

- Fulcrum (F): this is the pivot point or the hinge, where the movement happens so that the effort can move the load. In the human body this would be a joint such as the elbow.

The Three Types of Lever

The three types of lever are first class, second class and third class. What makes each one different from the others is the relative placement of the effort, load and fulcrum, which is to say the order they are in.

Here’s a handy table that explains the differences between them:

You can download this table here.

One thing you should bear in mind is that first class and second class levers don’t occur in the human body very often, and most gym exercises fall under the classification of being third class levers.

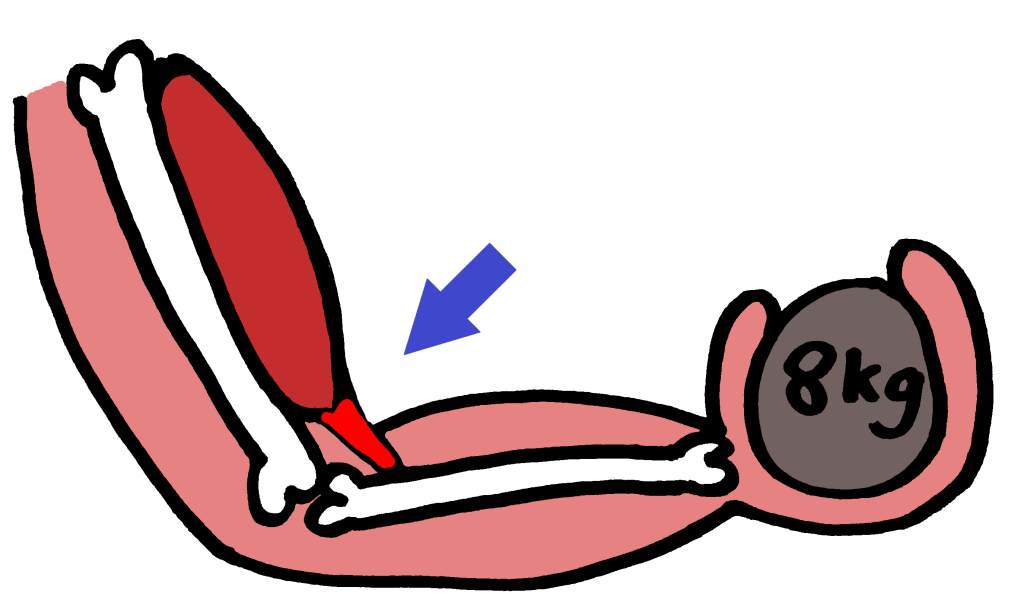

However, something you may well have difficulty getting your head around is that when deciding where the effort is you should be thinking about where the muscle attaches and not where the muscle itself actually is.

Look carefully at this picture of a bicep curl. Yes, the bicep muscle itself is to the left of the elbow (the fulcrum) but it crosses the elbow and attaches on the forearm, meaning that the effort is applied to the right of the elbow. Therefore, that’s where the effort is. If the muscle didn’t cross the elbow and pull on the other side of it then the movement couldn’t happen.

And Why Do You Need to Know This?!

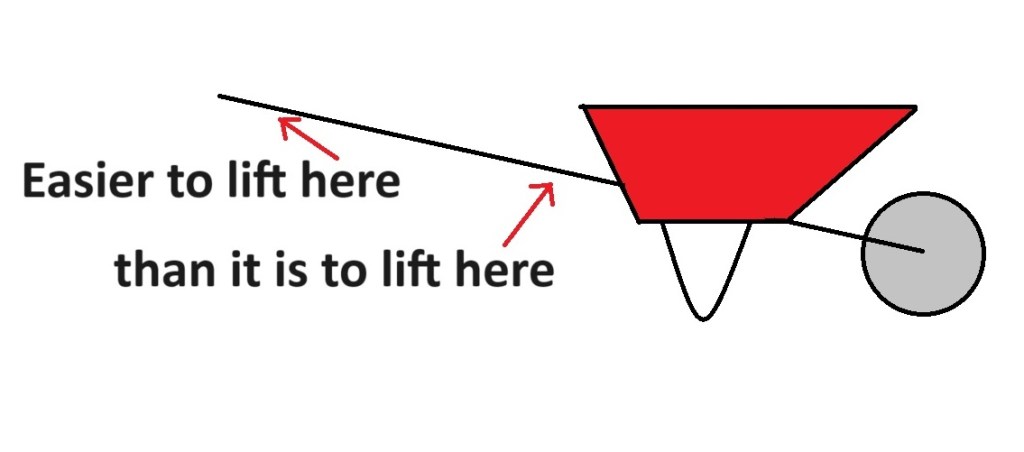

Well, once you’ve (hopefully) got your head around the above you might start to realise why knowing about levers can be of practical value. To examine this further let’s first of all establish a basic principle by looking at a real-life example of when a lever makes something easier: a wheelbarrow.

You’ll probably know that the longer the handles are on a wheelbarrow the easier it is to lift up. And if you try to lift a wheelbarrow by holding the handles closer to the load you’ll find it more difficult.

The underlying principle here is that when the effort is closer to the fulcrum, more effort will be required.

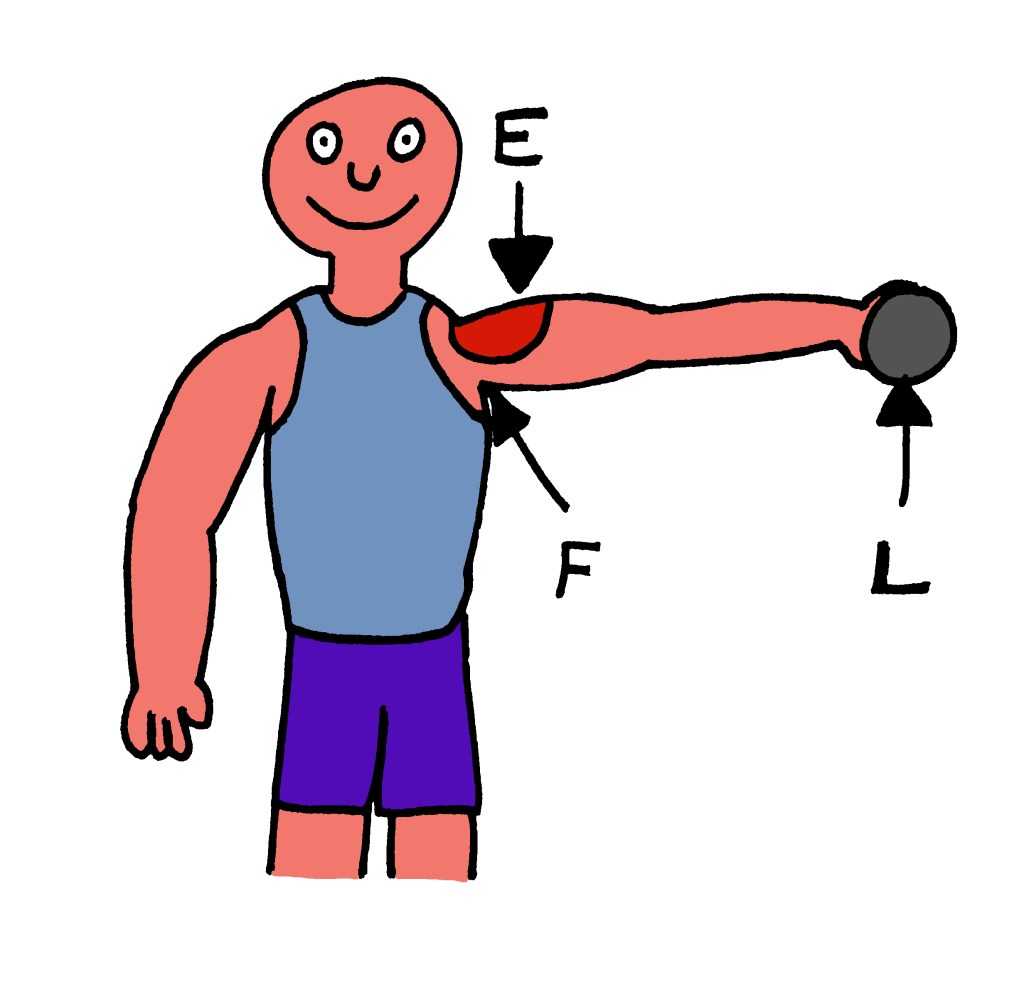

Let’s now apply that principle to the human body. If you’ve ever wondered why you can lift far more in a biceps curl than you can in a lateral raise it’s because of this. The main muscle in a lateral raise is the deltoid, which pretty much covers the shoulder but only attaches to the upper arm a short distance down from where it originates.

Therefore, this means that because the effort is close to the fulcrum you have to work harder to lift the weight when performing a lateral raise than you would if you were lifting it in a bicep curl. If the delts were longer and inserted nearer the elbow you’d find the move a lot easier.

So that’s why it’s of use to learn about levers: it gives you a better understanding of how the body works on a biomechanical level, helps with your anatomical knowledge by encouraging you to think about where muscles insert on bones and also encourages you to think about why this makes some exercises more difficult than others.

(On a more advanced level, the study of levers also goes some way to explaining why people with longer limbs can find it harder to put on muscle: there are biomechanical reasons why they have to put less work in to lift something, meaning the muscles don’t work as hard and therefore aren’t challenged as much, so that’s something you could look into if you had a particular interest in helping people like that build muscle, but that’s where things start to get really complicated…)